Recent advances in single cell proteomics and transcriptomics make it easier to collect single cell measurements across biological systems. The two most common methods are single cell RNA-sequencing and CyTOF. Although we will focus on scRNA-seq in this tutorial, the concepts important for single cell analysis generally hold across technologies. This is especially true for visualization, clustering, and differential expression.

Why single cell?

Single cells are one of the basic units of biology. We generally think of single cells as the things that act on themselves and surrounding extracellular structures to perform basic tasks such as moving appendages, processing external stimuli, defending the organism from infectious invaders, etc.. Because these units are so important for the function of an organism, it’s naturally to wonder how many different kinds of cells are in a specific tissue, how these cells change over time, and how cells differ between individuals.

Although the genome provides information for all these phenomena, it is the differences in expression of individual genes (at the DNA, RNA, and protein level) that account for differences in function across cell types. Because individual genes in individual cells effect functions in biological systems, one can understand why averaging expression across many cell types mixed at unknown ratios–as done in bulk RNA-seq–limits biological insight.

A brief history of scRNA-seq

Measuring gene expression in single cells has been around since at least 1992, when J. Eberwine et al. published the first single cell qPCR assay in Analysis of gene expression in single live neurons (1992). They measured expression of roughly one dozen genes in 15 neurons isolated from the brain of a rat and characterized two distinct populations based on ion channel expression. Shortly thereafter in 1998, developments in smFISH (single molecule Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) provided the a way to visualize expression of individual mRNA molecules in single cells (Femino AM, et al. 1998). smFISH remains the current gold standard for single cell RNA quantification and is used for validation of many scRNA-seq methods. In 2003, Kamme F et al. expanded the set of genes assayable in single cells using microarrays (Kamme F. et al. 2003). In that study, a groundbreaking ~4500 genes were assayed in 11 cells.

All the above methods rely on some method of hybridization to nucleic acid probes. It wasn’t until 2009, however, when RNA sequencing expanded single cell RNA profiling to the entire transcriptome (Tang, F. et al. 2009). This protocol and subsequent single cell protocols require the manual isolation of individual cells into PCR tubes for cDNA amplification. The time-consuming nature of this technique and high cost of preparing relatively large microliter-scale reverse transcription reactions kept dataset sizes down in the range of dozens of cells per sample. In 2012, Fluidigm introduced the C1 microfluidic device that (at the time) automatically captured up to 96 cells from a single cell suspension created single-cell libraries using nanoliter reaction volumes.

The biggest disruption to single cell transcriptomics arrived in the summer of 2015 when two groups at Harvard published independent microfluidics technologies to capture cells in nanoliter droplets (Macosko EZ. et al. 2015; Klein, AM. et al. 2015). The speed, scalability, and low cost of these methods suddenly made it possible to profile tens of thousands of cells in a single experiment. These droplet single cell approaches were commercialized by 10X Genomics in 2016 in their $125k lunch-box sized Chromium device (Zheng, GZ. et al. 2017). Since then, there have been several advances in single cell transcriptomics, including the ability to capture simultaneously cell surface epitopes and transcriptomes in single cells (Stoeckius M., et al. 2017) and efficient split-pool library preparation methods (Gierahn TM. et al. 2017). However, most of the data our lab analyzes comes from the 10X Genomics 3’ Single Cell library prep kit.

How to capture cells in droplets

Capturing mRNA from individual cells is a challenging goal. The first challenge is isoalting individual cells for reverse transcription. In droplet based methods this is done using a microfluidic chip. The following schematic from Zheng, GZ. et al. (2017) shows how this works.

*](/img/how_to_single_cell/10x_cell_capture.png)

Image from Zheng, GZ. et al. (2017)

The chip captures beads loaded with barcoded library adapters and individual cells into droplets. These droplets form an emulsion because they are suspended in oil. In the next image, you can see a single looped cell capture event on a DropSeq chip.

*](/img/how_to_single_cell/dropseq_capture.gif)

Image from dropseq.org

Here, a single cell (bottom) joins a bead in lysis buffer (left) as they flow through the chip. Oil flows in through the channels in the middle and pinch off individual droplets.

Although the exact nature of the bead varies between technologies, the basic idea is that each bead contains uniquely-barcoded adapters with: an oligo d(T) that hybridizes to poly-A tails, a cell barcode, a unique molecular identifier, and reverse transcription primers.

scRNA-seq library preparation

Although you probably know this, let’s start by reviewing the basic structure of an mRNA.

*](/img/how_to_single_cell/gene_model.jpg)

Image from APASdb

In the standard 3’ library preparation, the goal is to select for mRNA using the polyA tail. Selection is necessary because the majority of RNA in a cell consists of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA). We don’t want to sequence these functional RNAs because they don’t give us information about gene expression. To select poly-adenylated mRNA, the library adapters include a long stretch of thymines (Ts) that hybridize with the long stretch of adenines (As) in the polyA tail.

La Manno, G. et al. (2018) found that these library adapters also prime internally (i.e. more 5’ than the polyA) making it possible to sequence the introns of newly-transcribed pre-mRNA molecules facilitating the detection of actively expressed genes.

Following hybridization of adapters, the basic steps for library preparation are as follows:

- Cell is captured in droplet with bead

- Cell lyses in hypotonic buffer within droplet

- 3’ barcoded-adapter hybridizes to polyA tails on mRNA

- First strand reverse transcription (RT)

- Second strand RT

- PCR amplification

- Fractionation and size selection

- 5’ adapter ligation

- Final amplification

- Sequencing

The exact library preparation protocol will vary by technology (and version thereof). For a detailed explanation of the library preparation, consult technical documentation for whichever technology you’ll use.

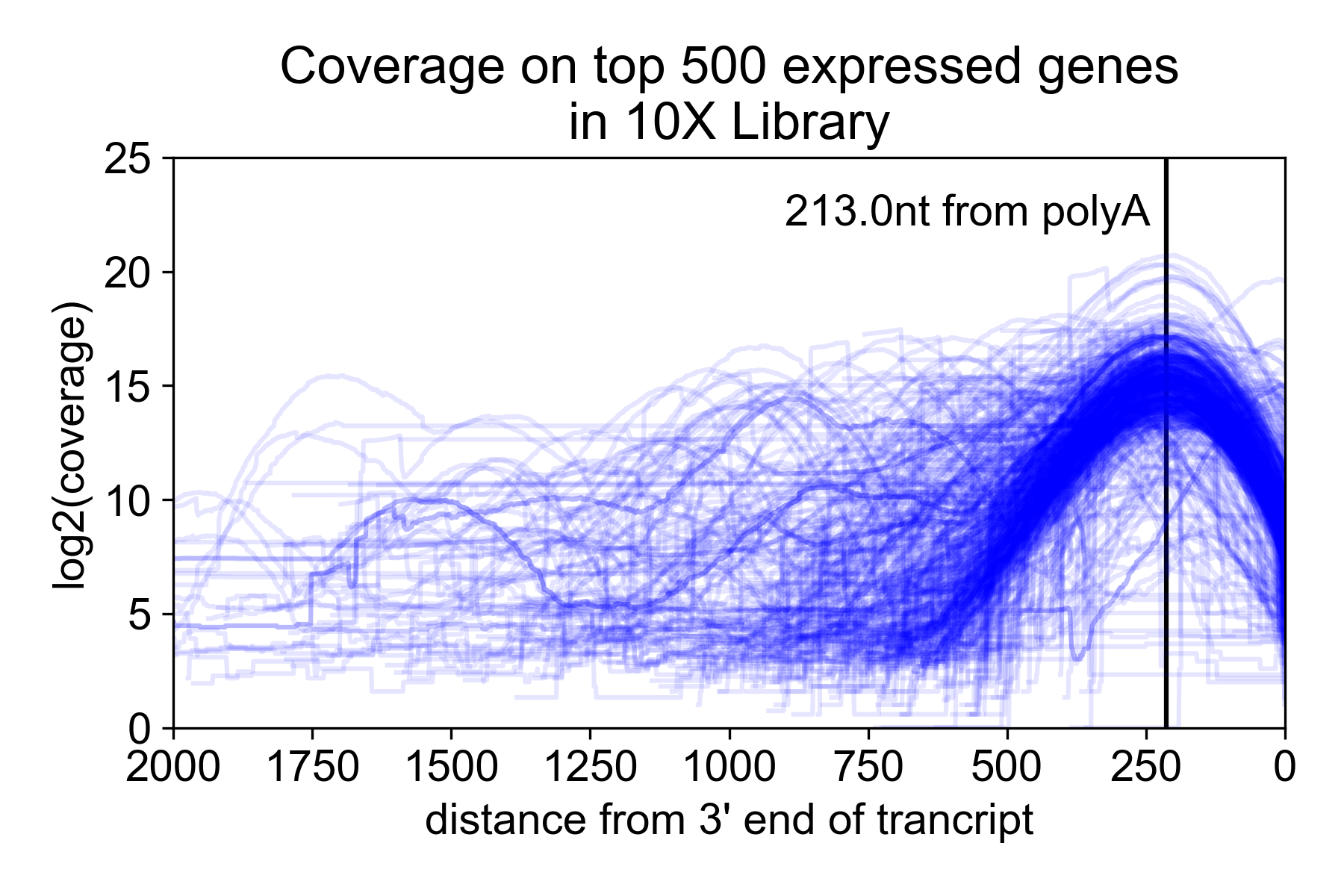

Because of the size selection and PCR amplification primed using the 3’ and 5’ adapters, the library is heavily 3’ biased with the majority of the read coverage falling ~200nt from the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNA. Note, however, that annotated 3’ UTRs do not always correspond to the actual isoform expressed in a sample. For this reason, you may get coverage “past” the end of the gene.

In the following plot, I took the 9K PBMC dataset from 10X Genomics and plotted coverage over the top 500 expressed genes relative to the annotated 3’ UTR.

Special considerations for single cell data

Single cell datasets are unlike most other biological datasets for several reasons. First, these datasets are large. When analyzing bulk RNA-seq data, it is common to have roughly 2 to 10 datasets. A massive dataset, like the one generated by the GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) consortium, might have 50,000 gene expression measurements. Compare this to the 1.3 million cells dataset generated by 10X Genomics in 2017. Even a lab with no experience generating large biomedical data can use scRNA-seq to measure gene expression in several thousand cells. The sheer number of observations in these datasets necessitate special computational approaches to analyze them.

Another reason that single cell datasets are challenging to analyze is they are high dimensional. Compared to more common single cell methods like FACS or single cell qPCR or microarrays, scRNA-seq datasets comprise many more features per cell. This makes it difficult to understand things like “which cells are close to which?” or “what genes are most similar?”. Thankfully, we can make some simplifying assumptions that make tackling these questions easier.

Single cell data is also noisy. In scRNA-seq, it is estimated that only 10-40% of the hundreds of thousands of genes in a cell are captured during reverse transcription.